History of

Tower

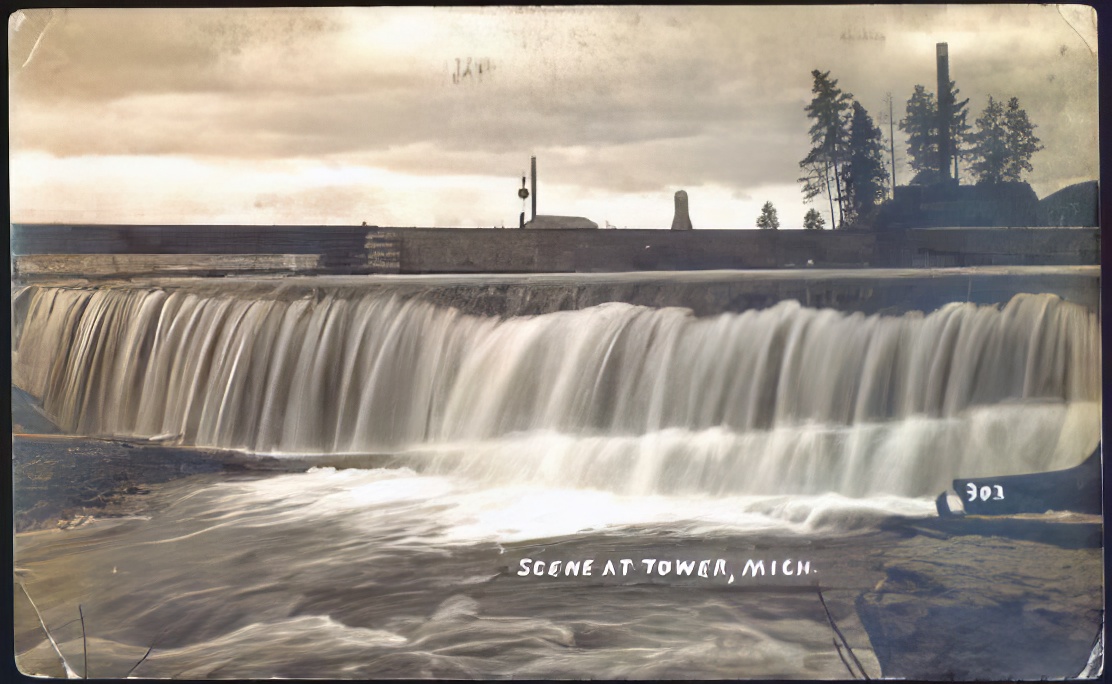

Photos submitted by Linda Dankert, from the photo album collections of the Pincombe and Ferguson families of Onaway and Casnovia, MI

It was named for the daughter of Judge Samuel S. Tower, Ellen May Tower, who died of typhoid fever as an army nurse in the Spanish-American War. She was one of the first women to volunteer her services to her country as a nurse and to be accepted. Ellen traveled to New York to care for soldiers who were injured in the war, and then on to Puerto Rico. There she was stricken with typhoid fever and died December 8, 1898. At that time in history, typhoid was almost always fatal. It quite often affected young people, and Ellen was only 30 years old when she died. Ellen was the first American woman to die on foreign soil in service of the United States. She was the first woman from Michigan to be honored with a military funeral with full honors. On January 17, 1899, over 3,000 mourners attended her service.

On April 28, 1899the post office was established in Cheboygan County, with James A. Kelley as the first postmaster. The local people honored Ellen May Tower by naming the village and the post office of Tower in remembrance of her.

Tower was originally platted on May 20, 1899, showing a town five blocks long and two blocks wide. The boundary was highway M-68, formerly listed as M-10 or M-23. Later an addition was platted south of the highway three blocks long and two blocks wide. Barclay, the main street, was lined with hotels, laundry, banks, a newspaper, blacksmith shop, livery stable, general store, barber shop, dance hall, post office, and fire department with their own horse drawn fire truck. Board walks lined the main street. Other buildings around town included churches, school, and seven saloons.

In 1910, Tower boasted a population of 800. It had a bank, one each of Methodist, Episcopal, and Baptist churches, a graded school, one hotel, handle, shingle, stave and saw mills, and a planing mill. The town had five saw mills surrounding the Tower Pond which producing lumber, handles, butter bowls, shingles, and staves. In winter ice-cutting was an industry. The pond ice was cut to store for railroad refrigerator cars as well as for ice for the community needs. Telephone and telephone connections were also present. Village Officers were: President-D.M. Myers. Clerk-John J. Kelley. Marshal-Thomas Clark.

Black Tuesday, July 11, 1911, has gone down in history as the worst and most destructive day that ever dawned on this part of Northeastern Michigan. The Au Sable-Oscoda fire, Michigan’s last large forest fire, destroyed the sawmill towns of Au Sable and Oscoda and nearly destroyed Tower, 113 miles north of those towns.

At that time, buildings in most of the villages in the northern part of Michigan were constructed mainly of wood atop heaps of sawdust and sand - wood cut from their forests and planed at their local mill sites during what was still the heyday of Michigan’s lumbering industry. There were no cement sidewalks; wood chips and sawdust basically made up the bulk of roads and walkways. They served the purpose well, keeping mud down on rainy days and providing traction for horses’ hooves during icy winter months. No one looked ahead and pictured these sawdust trails as prime fodder for run-away flames licking up dry tinder.

The summer season of 1911 was extremely dry and hot. Newspaper accounts and weather statistics indicate that the week of the fire, the Oscoda-Au Sable area was parched earth with numerous fires reported in parts of Cheboygan and Presque Isle counties, in Alpena, Waters, Alger, Turner, Boyne City, and other small fires in as many as ten northern Michigan counties. The front page cartoon of one 1911 Michigan daily newspaper showed a citizen knocking on the gates of hell pleading, "I’m looking for a cool spot." The devil answered, "Come in quickly and close the door." The Tawas Herald reported on July 7 that "Saturday, Sunday and part of Monday were among the warmest days known here in a long time, the mercury ranging from 94 to 100 in the shade.

For days smoldering forest fires that had been spreading through the slashings was by the wind that at times assumed a speed of forty miles an hour, fanned into flames, creating a smoke that was blinding to anybody that dared venture out. In the late afternoon of Tuesday, July 11, 1911, Deputy Game Fire Warden Ellsworth rode west from Onaway toward Tower only to find the worst conditions of this kind he had ever encountered. Facing a gale of wind, dust, and smoke that was blasting him at forty miles an hour, there were times when the horse could be hardly seen. As Ellsworth neared Tower he met people in rigs, on foot, or horseback, hurrying towards Onaway for fear of being devoured by flames. They warned him to flee for his life as they were doing, but he would not turn back. According to his own words, as published in the July 13, 1911 Onaway News, he drove into Tower and a more direful picture of a deserted village he had ever seen. Half the population had gone on the morning train to Cheboygan to see a circus, while the other half had nearly all fled or was getting ready to flee. Every kind of wagon, buggy, or carriage was brought into requisition to remove goods and people to safety.

By uncoupling a car at a time and moving them toward the mill eleven cars were saved for the D & M (Detroit & Mackinaw Railroad). The D & M’s loss of the Tower depot, agent’s house and twenty-four cars totaled $30,000. Fitzpatrick Brothers Shingle factory, stock on hand, including shingles and cedar was estimated at $7,000. The Worboys Lumber Company saved six cars of logs because of the efforts of Charles McGinnis. As reported in the News, "had it not been for half a dozen men of the McGinnis stripe, the huge piles of lumber, the mill and every vestige of Tower would have been nothing but an ash heap today."

Fire Warden Ellsworth was not saying much but put a lot of enthusiasm into his long handled shovel. He also acted as an angel of mercy later by carrying ice water to the fighters and staid on the job nearly all night. Behind his helmet of whiskers M. D. Myers was a handy man with the water bucket and never quit until danger was over. Cashier Fuehr showed us how to jam a crow bar under a car wheel and yank brakes loose. Lew Robbins, northwest of Tower, lost everything in the fire. Badder's little mill was wiped out along with his home and entire belongings. Nearby residents of Waverly Township, just north of Tower were subjected to a great deal of smoke and in many instances of narrow escapes from fire. Those who lost their homes were Samuel Wells, loss $400, Ira Fales, loss $400, Freeman Rose, loss $250, William Laidle, loss $600, Schoolhouse #3, loss $1,400, insured for $1,200.

Residents east and south of Tower also suffered losses. Just east of Tower, Joseph Goupie's place was swept from the face of the earth. His loss was $1,200. His house, barn, chicken and hog houses, two hogs twelve ton of cut hay, garden stuff, and all personal belongings were lost. Louis and George Wilton and William Bailey of south Forest lost their home and outbuildings, barely escaping with their lives.

The fire's devastation of Tower was never to be recovered from. For days, Tower, Onaway, Millersburg, Alpena, and Oscoda were all affected. The destruction was devastating to everything and everyone in its path. Communities struggled to rebuild with the help from the State of Michigan for their destitute. Michigan's southern population was quick to send supplies and help with the immediate needs for food and clothing. Help came from such cities as Detroit, Bay City, Grand Rapids, and others. The 1911 fire delivered the fatal punch to the fast-waning lumbering era in northeast lower Michigan. Many industries simply did not or could not afford to rebuild. A score of lives were lost, and damage amounted to $3 million. Coming so close, the fires awakened public interest and stimulated forest fire control. The Onaway News believed the origin of the fire was caused by boys in swimming and using matches to light cigarettes while sitting on logs at the river bank.

By 1916, Tower's population had dropped to just 300. It had two banks, a Methodist Episcopal and Baptist churches, a graded school, a hotel handle, shingle, stave and saw mills, and a planing mill. It also had telephone and telegraph connections. E.C. Burt was the postmaster. Village Officers were: President - I. Demorest. Clerk - E.J. Burt.

By the 1920s, the region's timber and mills were dying out. The town dwindled. But, the 1930s Depression brought people back to Tower and the surrounding area. They built tarpaper and pole houses and kept a cow, a couple of pigs, and grew a garden to feed their families until times got better. With the 1940s came World War II and the village grew and prospered. Rural electricity came into being and made for better living conditions. Mail routes and school bus routes were also forthcoming, and with that, better roads and power lines, creating work for laborers.

With thanks to Kevin Everingham who provided the initial base for this history of Tower. Parts of these works are sourced from his book, The Everingham Family of Michigan, 1999.

Copyright 2004- by MIGenWeb Project. All rights reserved.

Copyright of submitted items belongs to those responsible for their authorship or creation unless otherwise assigned.