by [William Chesbrough]

Submitted by Anita Gauld

All photos courtesy of Anita Gauld

Please Note: The story does not include the name of the author of the piece. The author name above is enclosed in brackets because I am guessing at the name from internal evidence in the narrative. If anyone knows definitely who the author of the piece is, please send it to the coordinator.

Update: Andrea Wilson reports that the author of this piece is definitely William Chesbrough. Wilwin was named after him and his brother Erwin, which the author mentions in the article. The author also mentions his sister Helen and her husband Fred; Andrea has identified them as Helen and Frederick Handy, of Michigan and California.

Your great-grandfather Alonzo Chesbrough, living in New York State, moved to Toledo, Ohio around 1870 and set up his four boys in the lumber business in upper Michigan, on the Tahquamenon River. He acquired then, or later, about 35,000 acres of timberland along that river, stretching from the mouth of the Tahquamenon on Lake Superior west to Newberry and north halfway to Whitefish Point. He also acquired sections of land around Fiborn Quarry, Henrie Pitt (N.E. of Fiborn, across the DSS&A tracts,), Wilwin country and even patches south of Wilwin across M-48 in the vicinity of Rexton. Mr. Hulbert, in his reminiscences of that northern country has said: "The Chesbroughs were probably the first to buy pine in the Tahquamenon River region. Their first purchase, in the 1870s, was for 93 million feet and cost $93,000. In all, they cut about 300 million feet in this vicinity - the finest grade of cork pine that money could buy." Incidentally, in talking about the beautiful pine forests, Abe Chesbrough, your grandfather's twin brother, used to tell a story of paddling down the Tahquamenon with an Indian in his birch bark canoe, around 1880. "It was just like floating down the aisle of a cathedral. The dense pine trees grew down to the water's edge and were so tall and so thick that the river, about 150 feet wide, seemed like a ribbon of water cut thru a dense forest."

The

first Chesbrough mill was located right at the mouth of the Tahquamenon, but

burned down within a year. They then moved it about four miles south and around

a point into a sheltered bay, and called the place "Emerson", after a partner

of your great grandfather's in New York State. The new mill was larger and they

built a small village consisting of a store, small hotel, office, four houses

for the four brothers, about 30 small mill houses and barns, cook camp, bunk

camp for men, etc. They spent over $100,000 on these, plus docks, plus a canal

running along the shore from the river down to the mill, in which to float logs.

Here they operated for the next thirty years and a very profitable business

it became. All shipping was by boat and one or two freighters could always be

seen loading lumber for lower ports, chiefly Tonawanda, N.Y. They even owned

one small freighter called the "Peshtigo." The mill ran from April to December

and logging was kept up all year round, but more heavily in the winter. Logging

camps were built on the Tahquamenon, at Hendrie Pitt and north near Whitefish

Point. Most of the logs were shipped, on their woods railway, to a place on

the Tahquamenon called "The White House" landing. Here were large bunk houses,

a railway shop, blacksmith shops, and huge log decks. Logs were stacked here

in the winter, dumped into the river in April, and floated down to the mouth,

then thru the canal to the mill. Occasionally the river would take on a late

freeze, and then the logs would pile up at the Falls fifty feet high and have

to be dynamited before they would loosen and go over the falls and on their

way. "Con" Culhane, a little Russian Jew, ran the woods railway and got out

most of the logs. He had a railway bridge across the river and parts of his

old grade can still be seen in the woods above the Falls. He was killed one

morning on his own railway; he was on a log car, crawling along, when the engine

bumped the cars hard, threw him underneath and cut him in half. They brought

his remains back to the camp before his poor wife was out of bed.

The

first Chesbrough mill was located right at the mouth of the Tahquamenon, but

burned down within a year. They then moved it about four miles south and around

a point into a sheltered bay, and called the place "Emerson", after a partner

of your great grandfather's in New York State. The new mill was larger and they

built a small village consisting of a store, small hotel, office, four houses

for the four brothers, about 30 small mill houses and barns, cook camp, bunk

camp for men, etc. They spent over $100,000 on these, plus docks, plus a canal

running along the shore from the river down to the mill, in which to float logs.

Here they operated for the next thirty years and a very profitable business

it became. All shipping was by boat and one or two freighters could always be

seen loading lumber for lower ports, chiefly Tonawanda, N.Y. They even owned

one small freighter called the "Peshtigo." The mill ran from April to December

and logging was kept up all year round, but more heavily in the winter. Logging

camps were built on the Tahquamenon, at Hendrie Pitt and north near Whitefish

Point. Most of the logs were shipped, on their woods railway, to a place on

the Tahquamenon called "The White House" landing. Here were large bunk houses,

a railway shop, blacksmith shops, and huge log decks. Logs were stacked here

in the winter, dumped into the river in April, and floated down to the mouth,

then thru the canal to the mill. Occasionally the river would take on a late

freeze, and then the logs would pile up at the Falls fifty feet high and have

to be dynamited before they would loosen and go over the falls and on their

way. "Con" Culhane, a little Russian Jew, ran the woods railway and got out

most of the logs. He had a railway bridge across the river and parts of his

old grade can still be seen in the woods above the Falls. He was killed one

morning on his own railway; he was on a log car, crawling along, when the engine

bumped the cars hard, threw him underneath and cut him in half. They brought

his remains back to the camp before his poor wife was out of bed.

Like you children at Wilwin, my earliest recollections were of summer vacations spent at Emerson - probably around 1900. We had our bathing beach, our fishing hole, our trips out into the bay on a little steam launch, our picnics along the shore, and an occasional boat trip to the Little Falls. This latter was a rare treat. We never went to the Big Falls in those days for there were no roads and nothing but a row boat could get above the Little Falls, and it was a four mile row against a heavy current. Even running the launch up to the Little Falls (seven miles) was a tough feat against a three or four mile an hour current.

Even getting to Emerson was a time consuming job. We lived in Bay City in those

days, and would take the sleeper at night and

arrive

in Mackinac City in the morning. It took some three hours to get across the

Straits on the car ferry S. S. Marie. There were no passenger ferries in those

days - the whole train was ferried across from St. Ignace we rode to the Soo

Junction, changed cars here and then rode to Eckerman, where we got off, about

one P.M. Here we had a box luncheon and then, in a six-passenger buckboard --

no top, with two horses, we started on the long sixteen mile ride to Emerson,

a 3-1/2 hour ride, if the narrow dirt road was dry, and a good 4 to 4-1/2 hour

ride if not. Emerson was reached about dinner time - "supper time" in those

Victorian days. Today, the trip by auto from Eckerman to Emerson takes about

20 minutes. Today, it is a macadam road, with little timber left to ride thru,

but in those days, the narrow dirt or corduroy road wound thru miles and miles

of dark, beautiful forests; huge trees rising on both sides, and the road running

down thru it like a ribbon. Deer were plentiful and once in a while, a bear

or a fox would ramble or dart across the road. We could hear the coyotes and

wolves howl, but rarely saw one, even in those days.

arrive

in Mackinac City in the morning. It took some three hours to get across the

Straits on the car ferry S. S. Marie. There were no passenger ferries in those

days - the whole train was ferried across from St. Ignace we rode to the Soo

Junction, changed cars here and then rode to Eckerman, where we got off, about

one P.M. Here we had a box luncheon and then, in a six-passenger buckboard --

no top, with two horses, we started on the long sixteen mile ride to Emerson,

a 3-1/2 hour ride, if the narrow dirt road was dry, and a good 4 to 4-1/2 hour

ride if not. Emerson was reached about dinner time - "supper time" in those

Victorian days. Today, the trip by auto from Eckerman to Emerson takes about

20 minutes. Today, it is a macadam road, with little timber left to ride thru,

but in those days, the narrow dirt or corduroy road wound thru miles and miles

of dark, beautiful forests; huge trees rising on both sides, and the road running

down thru it like a ribbon. Deer were plentiful and once in a while, a bear

or a fox would ramble or dart across the road. We could hear the coyotes and

wolves howl, but rarely saw one, even in those days.

Well, Emerson flourished - flourished too well in fact, for in 1912, the four brothers split up. Free and Aaron took the mill at Emerson, and Abe and Frank, your grandfather, took their shares in timber lands and moved out. Abe selected lands largely up and around Whitefish Point, while your grandfather took his around Fibron, Hendrie Pitt, Wilwin, Rexton, and west of Wilwin. Emerson had made them all rich in 30 to 35 years.

Two years went by and finally your grandfather, much like the sailor retired from the sea, hankered for his job once more. The woods were in his blood. He decided to build another mill to cut the timber he now possessed and to take your Uncle Erve and me into the business with him. There was an old mill at St. Ignace he thought he might buy (Jones Lumber Co.), but they wanted too much for a run down plant, so he decided to build. At Athens, Michigan (S.W. Corner of State) was a mill for sale and the machinery was in pretty good condition, so he bought it. Next question - where to put the mill? All his timber was in the Wilwin region, so the mill must be fairly close too. The St. Ignace mill was out of the question. (Too bad, for it was probably the best location - labor and shipping considered) and there was no other ready built mill available. An idea struck him. Up on Sect. 13, in Town 44-7, was a heavy ridge of limestone land. Why not build a mill there and also a stone quarry, using mill refuse the run the quarry? Thus have two businesses with the refuse from one to run the other.

At that time, Fibron Quarry was operating 10 hours a day, six days a week. Owned by the Algoma Steel Co., Canadian Soo, it supplied limestone for fluxing iron ore to steel mills in Canada, and on the Great Lakes, shipping about thirty cars of stone a day, or about 1500 tons - profit 50 cents a ton or $750 a day. He thought he could do the same, as good stone was in demand, and the demand was increasing due to the war in Europe - just starting.

So, in the fall of 1914, he sent one of his old logging jobbers, Frank Weston, up to Section 13 to get some limestone samples. Weston arrived at what is now Wilwin about October and pitched a tent about where the old water pump is, opposite the Lodge. During the winter, he proceeded to dynamite four or five huge pits, about twelve feet deep along the limestone ridge, sending samples of stone to Detroit for analysis. The stone was good, testing out 98 degrees fine lime - wonderful for ore fluxing. Today, three of these pits are still in use - one on the road going out, for refuse, one for our outdoor "John" behind the office, and one for the sewer outlet for the Lodge. The others, back in the woods, have been covered up by logging operations. Frank did a good job, but almost lost his life in the process. One day, at the ten foot level of a hole, he jammed his dynamite into a crevice, lit the fuse, and started to scramble up his wooden ladder. The ladder broke and Frank came tumbling down on top of the dynamite. He sprang to his feet, stuck his foot in a crack and made a flying leap, landing on the top edge of the hole as the dynamite let go. It blew him six feet away and tore the coat off his back, but beyond a sore arm, he was intact. A very close shave.

Your grandfather was satisfied - here he would build both mill and quarry. One snowy, blustery day in the middle of January, 1915 (it was the 19th I believe) your grandfather, Erve, Frank Weston, and myself and two woodsmen were dropped off the DSS&A afternoon train in a snow bank at a spot we later called "Chesbrough Siding." It was north and about two miles from that limestone ridge in Section 13 and the closest it came to the R.R. We, and our baggage, landed on a little hill, and the snow came up above our waists when we landed.

All around us were the "Uhlan Spears" of fir trees with a forest on one side and a tangled swamp on the other, and snow, snow, and snow on all sides as far as the eye could see. The scene was oppressive, and the thermometer stood 0 at 10 below 0. Not a very pretty picture for a recent Yale graduate!

Well, the men cut some poles and made the framework for a small room, 10 x 15, over which we stretched some canvas. This was our home for the next ten days. We ate in it and we slept in it; a small kerosene stove did the cooking and kept us warm, if you could call it "warm," and camp beds did the rest.

Next day we finished up our camp, and the following day, we started out to blaze a trail thru the woods to our mill site. Our trail later became our tote road from the siding to the mill. This trail blazing was slow and tedious because we had to find a level way and a straight way, so far as possible, to our goal, and the snow was so deep, it was tough work. Only an approximate compass course would work and all the time, it meant shoveling and shoveling and shoveling thru about three feet of snow. It was only about two miles to go, but as I recall it, we spent over three days getting thru, and we had to come back to our tent each night.

When

we arrived at the future "Wilwin", it was nothing but a long, low limestone

ridge, covered completely by heavy hardwood. The Wilwin you know has open spaces

- the mill yard, old pump site, barn site, village, and spot where the Lodge,

office, and carpenter houses now are. But in 1915, this was all covered with

heavy timber. There was a little open space where the water pump is in the field

and more open space down where we planted the trees, but the rest was forest.

The hill on which the Lodge and other buildings stand was heavy forest and the

whole mill site was solid hardwood. Only one pleasing site met the eye. Nestled

among the trees, about where the old root house is, near the pump, was a little

woodsman's shack, built and owned by a trapper named Harry Hart. It was of logs,

about 15 x 20, with a stove pipe chimney, windows in the sides and plenty of

snow on the roof. A coyote hung out in front and several skins were stretched

on the cabin wall to dry. Harry Hart, about 35, had started trapping in the

lower peninsula, had decided it was too civilized, so had moved to his present

site about three years before we arrived. He joined us and worked at the building

of Wilwin for over a year, then decided this place too, was becoming too civilized

and migrated to Canada. By 1917, all trace of him was lost.

When

we arrived at the future "Wilwin", it was nothing but a long, low limestone

ridge, covered completely by heavy hardwood. The Wilwin you know has open spaces

- the mill yard, old pump site, barn site, village, and spot where the Lodge,

office, and carpenter houses now are. But in 1915, this was all covered with

heavy timber. There was a little open space where the water pump is in the field

and more open space down where we planted the trees, but the rest was forest.

The hill on which the Lodge and other buildings stand was heavy forest and the

whole mill site was solid hardwood. Only one pleasing site met the eye. Nestled

among the trees, about where the old root house is, near the pump, was a little

woodsman's shack, built and owned by a trapper named Harry Hart. It was of logs,

about 15 x 20, with a stove pipe chimney, windows in the sides and plenty of

snow on the roof. A coyote hung out in front and several skins were stretched

on the cabin wall to dry. Harry Hart, about 35, had started trapping in the

lower peninsula, had decided it was too civilized, so had moved to his present

site about three years before we arrived. He joined us and worked at the building

of Wilwin for over a year, then decided this place too, was becoming too civilized

and migrated to Canada. By 1917, all trace of him was lost.

We repaired an old abandoned logging camp at the siding and moved into it from our tent during that winter, spending three months building a wagon road right into the mill site and blazing and hewing out a R.R. right-of-way at the same time. This R.R. blazing was a tougher job than the road, for it had to be straight and level. This meant hundreds of trees to be cut down and stumps to be blown out, hills to be graded and hollows filled. We had a working crew of a dozen men by this time, and the work went steadily, if slowly, along.

About mid April, we built our first men's camp at Wilwin and started our office. These buildings were built of eight foot long six inch logs nailed upright over a wooden floor, with open, log rafters and a wood roof. Iron double deckers were the beds and a pot-bellied iron stove furnished the heat. Chinks in the logs were plastered and later walls were covered with Celotax. The men's camp had wooden bunks with straw mattresses and a cook stove helped the pot-bellied one furnish heat. Tables and chairs were all made of tough lumber and lights were kerosene lamps.

The first machinery now began to arrive and was hauled in from the siding on sleds by two and four horse teams. The boilers came in hard. They were so heavy they broke the slush snow and bogged down, deep into the road. It took two days to run one boiler the two miles~ During April and May, all the big machinery was hauled in and work on the R.R. grade progressed, as did work on the foundation posts of the mill. In June, our engine, "Old 100" arrived and with her, we started to finish the R.R. We layed ties by hand for the first one hundred feet, then spiked rails on these, then ran the locomotive along and layed ties and rails from a flat car as she shoved it ahead thru the woods. Once started, this went fast and I recall we laid the whole two miles of rail in about ten days. It was putting in the rough grade that took the time. All that early summer, the engine was wood-fired and it took two men all their time to furnish the wood. Coal arrived eventually and we used it also in our stoves.

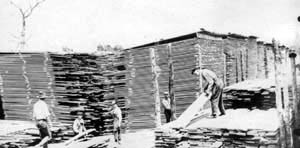

Cleaning

the mill site was a dynamite job in large part, after the trees were cut down.

That's the quickest way to get rid of stumps. The trees were hewed into 8" and

12" timbers for the mill frame and mounted on poured concrete piers in which

a piece of pipe protruded to lock into the end of each timber. These squares,

with their pipe ends, can still be seen all over the old mill yard after nearly

fifty years. We worked on putting up the mill, the concrete boiler house and

the blacksmith shop all summer. Then we dug out the mill ponds and bored our

wells to fill them. The mill was a huge framework of timbers 12x12 and 12x8,

with corrugated iron covering and a corrugated iron roof. About October, we

started installing the machinery and the boilers and before Christmas, it was

complete. We cut no lumber that late fall, but continued to clean land and build

the lumber trains behind the mill, the permanent men's camp, cook camp, barns,

and office. Winter came down hard, and eventually, all work stopped, so we started

to build two logging camps - one out north of the siding, and another south

of the "tunnel trail" known as Camp 2. This camp was about six miles south of

Wilwin over in the direction of Rexton. A fellow named Christenson operated

one and a Mr. Britton the other. Huge red logging wheels (12 feet high) were

bought, horses and tools acquired, and logging started in earnest right after

Christmas.

Cleaning

the mill site was a dynamite job in large part, after the trees were cut down.

That's the quickest way to get rid of stumps. The trees were hewed into 8" and

12" timbers for the mill frame and mounted on poured concrete piers in which

a piece of pipe protruded to lock into the end of each timber. These squares,

with their pipe ends, can still be seen all over the old mill yard after nearly

fifty years. We worked on putting up the mill, the concrete boiler house and

the blacksmith shop all summer. Then we dug out the mill ponds and bored our

wells to fill them. The mill was a huge framework of timbers 12x12 and 12x8,

with corrugated iron covering and a corrugated iron roof. About October, we

started installing the machinery and the boilers and before Christmas, it was

complete. We cut no lumber that late fall, but continued to clean land and build

the lumber trains behind the mill, the permanent men's camp, cook camp, barns,

and office. Winter came down hard, and eventually, all work stopped, so we started

to build two logging camps - one out north of the siding, and another south

of the "tunnel trail" known as Camp 2. This camp was about six miles south of

Wilwin over in the direction of Rexton. A fellow named Christenson operated

one and a Mr. Britton the other. Huge red logging wheels (12 feet high) were

bought, horses and tools acquired, and logging started in earnest right after

Christmas.

When spring came, we started the houses in the village and by fall of 1916, had built about fifteen, plus a school house and a church. Wooden sidewalks ran from village to mill and from boarding houses to mill. None remain now, if fact, by the time you children first visited Wilwin, around 1935, everything was gone but the office, the carpenter house, the Lodge office and warehouse.

Operations started early in 1916, and after many trials and breakdowns, the mill was running 100% about June 15th. It was during this period that lumber buyers started to come in and one was from Ford Motor Company. He liked our lumber, but didn't like staying in Trout Lake - said he got a dose of bed bugs staying at Clue Smith's Bar and Hotel - said he was "through" with the U.P. This gave us an idea - why not build a bungalow, or lodge, for us to live in, plus extra rooms for lumber buyers when they came in? We could feed and board them a day or two and with more congenial surroundings, they might prolong their stay, and thus buy more lumber. We could also have a place for father and mother to stay and a place for Fred and Helen, if they visited us, plus anyone else who might come up from Detroit.

I made a plan and we started to clear that hilltop where the Lodge now stands in the late summer, and the "Bungalow", as it originally was called, was started about September. It was up to the second story before winter closed in, and just about the time I realized I had forgotten to put in the stairs to the second floor, we quit for the winter. In the spring, we started the second floor, with snow still on the ground and Jim Flynn, our blacksmith, hammered out those marvelous door hinges, still visible, for the front door. John Burns, the mason, laid up those chimneys, and consumed about a quart of whiskey a day in so doing. I didn't like that, and told the foreman, Ollie Sayles, to take his whiskey away, but he said, "Bill, leave him alone, he doesn't get tight, just sips and sips all day long, and if you take the whiskey away, he'll quit, and you'll get no fireplaces." The whiskey remained. By September, we moved in. The electric lights were beautiful and it had a glow to it we hadn't seen in our day. Long, indirect, bowl shaped chandeliers hanging from the high ceiling, horn lanterns under the balconies, bronze, indirect chandeliers in the dining room, and lights in the kitchen, pantry, and all bedrooms. Also, black horn lanterns on the outside porch which glowed prettily at night. Current was from the mill dynamo.

We had a good crew at Wilwin, probably sixty or seventy all told, a fine group of families in the village and a good school. Wolves and coyotes bothered us a little our first winter. One Sunday night, they treed a couple of men walking in from Trout Lake, but they clamored down at dawn and got in all right. Deer were plentiful on all sides, and occasionally a bear would sneak into the village at night looking for garbage. One night, our three hundred pound cook (five feet high and five feet around) carried out a huge dishpan of garbage to dump into the barrel we had at the rear of the cook camp. She had done this every night for six months and could spot that barrel in the dark like a spots his bearings. Well, this night she got to where she knew the barrel was, saw an object blacker than the blackness of the night, and dumped the pan upside down, right on the back of a huge black bear, eating his fill at the barrel. There was a roar, heard in the men's camp, then a woman screams, heard almost at Trout Lake. The bear rushed to the woods, garbage all over him, and the cook broke for the kitchen. Next day, she quit - no more bears for her!

Running a mill in 1916 and 1917, or rather a lumber business, was a good job. We'd get up at the second mill whistle, (first one at 6 A.M., second at 7 A.M. to start the mill) have breakfast and then if no breakdowns occurred, I'd get on my little mule, "Mike" and ride out to one of our logging camps, either beyond the siding, or out at Camp 2. Both were five to six miles away, and the early morning ride was a delight. The woods at that time in the morning were awakening to life. Birds, squirrels, and rabbits on every side, and an occasional deer running across the road in your front. Everything was green and fresh and fragrant and made one glad to be alive. Arriving at the camp, you'd see what was being cut, how -many logging cars would be sent in that day, then you'd pay some camp bills, and start back, perhaps scattering a flock of pats on your way. Birds were plentiful in those days and fairly tame, sometimes they wouldn't even rise off the ground. I can remember Peg Worcester, about 1935, sitting on a stump on the R.R. grade talking to me when a flock of eight or ten birds broke thru the brush behind her and strutted right across in front of us, not forty feet away. I remember your mother, at another time, when we were courting in the woods, exclaiming, "Why, Bill, what funny chickens!" As half a dozen walked cackling, across our path. They were very tame, compared to later years.

Arriving back at the mill, it was lunch time, and boy, could we eat! About 2 P.M., the mail came in and it was office work until about four; then a tour of the mill and the trains to see what was out that day. The mill closed down at five and we ate dinner at six. It got dark too early in the fall to do much out of doors after that, so it was reading or listening to our old gramophone for the rest of the evening. Sometimes they were long and monotonous - the only part of the day that was - but we managed, with Al Jolson's records, to last until ten, and then to bed. Our electric lights, run by the mill dynamo, were turned off at 10:30, unless we had company, so all Wilwin was tucked in by 11 P.M. or before.

Wilwin got it's name by accident. When we went north, the siding was called "Chesbrough Siding" and the mill "Chesbrough's Mill." But there was a mill at Emerson called "Chesbrough's Mill" and father's brother had a mill at Manistique known as "Chesbrough's Mill", so things were a bit confused. I finally got the idea of taking the first three letters of my first name, Will, and combining them with the last three letters of Erwin's name and came up with the word, Wilwin. It was euphonic and it stuck, and Wilwin it was ever after. As Billy Rice, an Englishman from Escanaba said, "Wilwin" that has a British ring to it - all power to you!" (England was then up to her neck in World War I and winning was everyone's hope.)

We never built the stone quarry - the main reason the Wilwin site was selected. After the mill was up and operating in 1916, we ordered the stone crushing machinery, but we were then almost in the war ourselves, and "war priorities" prohibited our getting any such machinery for the next four years. By that time, the government had built up Calcite (on Lake Huron) to such an extent that when the war ended, they had more production capacity than customers and stone prices dropped from $1.00 a ton to 50¢ and less. No independent would operate on such a price, so the quarry idea was abandoned. Eventually, prices dropped and dropped until Ozark Quarry closed and finally Fiborn, "temporarily." But "temporarily" meant "forever" for both of them.

We had many mascots. One a cub bear we called "Little Bo" was the star attraction during 1916-17. He had a dog collar and would stand up on two feet and eat peanuts and would "roll over" for the same fare. For two years, he was our star boarder, but as he grew older, he got ugly and we had to let him go. Nearly each spring, we'd catch a fawn, feed it until it became tame, then put a bell and ribbon around it's neck. Most of them would hang around Wilwin for a year or more before disappearing - eating lettuce and tidbits out of your hand. I remember one little deer disappeared in the hunting season and upon coming down to breakfast one morning, there was the little thing dead upon the front porch. Some hunter had shot it, and it had run back to it's "home" before expiring. Many tears from the women on this episode. Mike, my little riding mule, was also a pet. He would trot you all over Mackinac County, never tiring, his gait being as easy on you as a rocking chair. But Mike was stung by a bee one day, with me on top, started kicking and landed me in a heap with a broken collar bone. After that, he wouldn't let anyone on him, unless backed into a corner and held. So I had to give him up, after being thrown off a couple of times and walking all the way home. I got a saddle horse after that, but the winters were too cold for him and he died, after that, I used the locomotive.

In the summer of 1915, we had our worst of many forest fires. Had we had all our buildings up, it probably would have leveled Wilwin. It started over behind the men's camp early one morning - probably from a careless smoker - and before everyone knocked off work to fight it, it was roaring thru the slashing great guns, threatening the cook camp, men's camp, and barns. We had hose and water at the mill and kept it away from mill and lumber, but it burned down toward the village and out toward the R.R. grade. Only by back-firing and digging trenches and filling them with water could we control it. It burned hard for two days and smoldered for a week until a heavy rain eventually put it out. You can still see signs of our trenches away across the fields to the north of the Lodge and nearly a half mile from it, across the old village road and up to the R.R. grade, a deep furrow standing out after 46 years.

Well,

that's the story. We operated until 1922 when we ran out of timber near the

mill, and as we had a severe depression in 1921, father felt it unwise to buy

more timber until things picked up. Before this happened, father died and before

his estate was settled, the Great Depression was on, and lumbering all over

Michigan received it's death blow. In 1919, there were ten mills operating in

the St. Ignace, Newberry, Soo area. In 1933, there were only three, and today,

not one - barring some small circular saw outfit run by a man and his family.

Lumbering, as big business, had left Michigan and gone Northwest. We kept the

mill in operating condition until 1927, when it became clear we couldn't, or

shouldn't, start up again, so we sold all mill machinery, railroad iron locomotive,

etc. Village houses were partly torn down, sold, to Trout Lake and the vicinity,

where they were reassembled. The church was removed to the corner of M-48 and

the Wilwin R.R., and the dismantled and burned, the concrete boiler house being

blown up.

Well,

that's the story. We operated until 1922 when we ran out of timber near the

mill, and as we had a severe depression in 1921, father felt it unwise to buy

more timber until things picked up. Before this happened, father died and before

his estate was settled, the Great Depression was on, and lumbering all over

Michigan received it's death blow. In 1919, there were ten mills operating in

the St. Ignace, Newberry, Soo area. In 1933, there were only three, and today,

not one - barring some small circular saw outfit run by a man and his family.

Lumbering, as big business, had left Michigan and gone Northwest. We kept the

mill in operating condition until 1927, when it became clear we couldn't, or

shouldn't, start up again, so we sold all mill machinery, railroad iron locomotive,

etc. Village houses were partly torn down, sold, to Trout Lake and the vicinity,

where they were reassembled. The church was removed to the corner of M-48 and

the Wilwin R.R., and the dismantled and burned, the concrete boiler house being

blown up.

Only the office, carpenter house and the Lodge remained. Wilwin had ceased as a business, but was just emerging as a glorious summer home for the Chesbrough families. A home and forest playground that was to serve the next generation for thirty-five years - until it was sold in the fall of 1962 to Ernest and Walter Riipi of Houghton. Thus ends the Story of Wilwin.

Toast to Wilwin

by W.J.C.

At Last Dinner of the '62 Hunting Season — and Last Party

Forty-seven years its stood there,

Forty-seven years last springtime

In its solitary grandeur.

Nestled there among the fir trees,

First, the oldsters who built it

Lived among its lights and shadows.

Then their children came and played there,

Fished near streams and shot at partridge.

Sharing all its joys and sorrows

Then their kiddies came and loved it

And their laughter rang triumphant

Over all that forest hardwood.

There's that great big, friendly pine tree

And the Tunnel Trail of memory.

Then the Synider Road and Village

Worcester's Acres and the Rail Grade

And that great black house of split logs

With its massive stone fireplaces

With its balcony and bedrooms

With its wrought iron hinged front door

And its living room of memories —

Memories long we'll have of Wilwin

Memories full of joy and living

Memories that will not be forgotten —

Here's a toast to Grand Old Wilwin

May you live on and on, forever

Giving joy to your new owners

As you always have to Chesbroughs!

In writing the story of Wilwin, it would not be complete without paying our respects to the Carpenter Family who were associated with us there for forty-seven years, two generations of them in fact.

Jason

Carpenter was one of our first employees; he worked on the R.R. grade during

the summer of 1915, then helped in the construction of the mill. That finished,

he operated the locomotive, "Little old 100" for some time; later, he was night

watchman, and later still, engineer in charge of all operating mill machinery.

After the mill was shut down, he remained at Wilwin as general watchman and

upkeep man for all idle machinery; he also had charge of the crew who tore the

mill down and shipped out the machinery and railroad equipment in 1927.

Jason

Carpenter was one of our first employees; he worked on the R.R. grade during

the summer of 1915, then helped in the construction of the mill. That finished,

he operated the locomotive, "Little old 100" for some time; later, he was night

watchman, and later still, engineer in charge of all operating mill machinery.

After the mill was shut down, he remained at Wilwin as general watchman and

upkeep man for all idle machinery; he also had charge of the crew who tore the

mill down and shipped out the machinery and railroad equipment in 1927.

From 1928 until his death in 1935, Jason was our caretaker and kept the Lodge and other buildings in good condition for our summer vacations and our fall hunting parties. Well can I remember his standing in the road, below the gate, one wild and rainy October night as the hunters drove up to see a huge lake across the road, and in the middle of it, a pile of old straw mattresses from the abandoned bunk house. Jason had corduroyed the road with them, and as each car pulled up, he would yell: "Back up, then gun her hard over the center of the mattresses!" As each car did that, a wall of spray rose up, completely covering Jason, and a plentiful supply of mud too, as the cars slid and spun their way to higher ground. When the last car made it, Jason was a sight, mud from head to foot and wetter than the lake.

He died in 1935 and Mrs. Carpenter took over. For many years, she kept the Lodge clean and in fine shape, with Warren cutting the wood and doing the outdoor work. Finally, she moved permanently to Trout Lake and Warren took over. This, fortunately, or unfortunately, led to his undoing.

One summer, we hired an attractive young girl from Detroit to come to Wilwin with us and look after the girls and teach them and the boys to swim; Pat Humphrey was her name. From then on, I noticed Warren had more work to do around the Lodge than he ever had before. The girls play house is the best example. Pat seemed unconcerned and seemingly indifferent, but Warren was persistent. The more he pressed his suit, the more unconcerned was Pat (like most women when they begin to like a fellow), but Warren could not be shaken off; he got his girl.

After this, Perry took up the job of caretaking and he carried it on until Wilwin was sold in 1962. Thus ended 47 years of service and devotion to the Chesbrough family. Dick can attest to this, for if ever a fellow had more pies baked for him, or more meals cooked for him by "Ma Carpenter," I never heard of it.

Anecdotes of Wilwin

Trout Lake, Michigan

Trout Lake, in 1915 was a thriving village, a little larger and much more prosperous than in later years. Lumbering was in its full stride and the saloons and cheap hotels were crowded day and night. The main hotel and saloon in those days was Clue Smith's. It was a large three story hotel - larger than any other building in Trout Lake today, and stood where Emil's grocery store now is. Clue was tough, hard-boiled, and made all his money on his saloon. The bar occupied the ground floor front of the hotel, and was about 30x50 feet long with a bar running the whole fifty feet. On Saturday and Sunday nights, (there was no closing on Sundays in those days) that bar was crowded with lumberjacks and whiskey was 25 cents a glass! (one ounce) The men were rough, the whiskey "rot-gut" and the clamor and noise was awful. Usually by twelve o'clock, half the inmates were drunk and by three - closing time - three quarters were on the floor. In the passage behind the bar was a broad, wooden stair, some ten feet wide, leading into the basement. Over one half of the steps, planks were laid to slide things to the bottom. As men got too drunk to stand, one of the bartenders would grab him, drag him to the steps, and slide him into the basement - where he could snore out his drunk. No proof was ever obtained, but rumor had it that Ollie's wife would go down into the basement after the hotel closed up and "roll" the drunks lying there of their money - what little they had left. Many men at Wilwin had this experience and many claimed they had been "rolled," but no proof could be obtained. I had a running feud with Ollie over this that lasted several years, but the result was only "bad blood" between us. Eventually, Clue's hotel burned down one winter and Ollie moved to Canada. That helped.

One of the assistant bookkeepers, Chet Keegan, by name, brought a brand new Model-T Ford to Wilwin in 1921. This was "somethin." Every Saturday afternoon and Sunday, he took some of the Wilwin residents for a ride; all wanted to go, altho there were few roads, all dirt or corduroy, and, literally, no place to go. One day Chet invited me to ride to the Soo, and we started out very early. It was 120 miles over and back, all of it over a narrow, rough, winding dirt road; no small part of which was corduroy. Today, on the modern highway, you can go over and back in a little over two hours, but in 1921, the time might be six or seven hours unless you had to change a tire or two, or the engine conked out, then the better part of the day was used up. Well, we got along fine to Rudyard and were spinning along outside the town at about 15 mph when to my astonishment, I saw our right front wheel rolling swiftly out in front of the radiator. I yelled to Chet to "look!" and he, startled at the sight, jammed on his brakes. That wasn't the thing to do, with a lurch, the car did a 90 degree turn to the side of the road and slid into the ditch. Fortunately there was no top, so while both of us were thrown out, neither of us got a scratch, but we did a three mile hike back to town for help, and it was many hours later before we could tow the car back, leave it, and take a team to Wilwin.

Trout fishing in the early day was no problem. Most of it was done on Sunday and the three steams were our standard places, the Davenport, Carp, and the Black River. Usually we didn't take a pole or reel, but would wind our lines on a spool, sit on a log or brushwood, and drop our line in any hole we saw - worms were the bait. Usually, there were so many fish that we could get our limit during the day, in spite of crude approaches to the streams and very little "finesse." Fish were small, running between seven and twelve inches. It was different on the Black. Here we used a pole (almost at the mouth of the river) and cast worms out into the middle of the stream - about four feet of water. At times we got nothing, but at other times, we'd get a half dozen beautiful rainbows-some thirty inches long. This was long before the highway was built (M-2) and the stream was fairly heavily wooded. Sometimes we'd take a lunch and go up to the east branch of the Taquamenon. Fishing was good there, but the distance was great, the roads bad, and the Davenport was about as good. Later on, Phil Worcester and I used to fish the Betsey, and you boys remember the ever memorable day the three of us, plus Warren, took one hundred perch out of East Lake in half a day! Alas, those days are gone forever.

Dick will ever remember Davie's shack. Davie was a teamster at Wilwin and worked there, alone, for one or two years. He used to go hunting out in the swamp to the west of the Village, and, liking the country, he built himself a log cabin, barn, and outhouse on a small hill beyond the swamp. He installed a wife there and eventually had a little daughter. They lived there until Wilwin closed, then migrated. Year later, Davie's shack became Dick's pride and joy, and years later, Davie's daughter became, and still is, Phil DeGratfts head cook at Trout Lake.

Deer hunting was the big event every fall and a lot of lumber buyers showed up with guns. They'd go out every day, with a lunch, and about one out of three got a deer. Many were temporarily lost, and old Erwin Ladd, the conservation officer, spent a lot of time around Wilwin dragging them out of the woods. I remember two fellows from Flint were lost for two days and came out on the highway at the end of that time almost over at Strong's - 5 miles away. Fortunately, in all those years, no one shot himself. I never shot at a deer, used to go along with some of these parties, but never carried a gun. One day, I saw "buck fever" in its best form. Went out with Chet Keegan and a group toward the siding. Pretty soon we heard a shot and a yell to our right, then a crashing noise in the woods. Chet jumped up on a stump, his gun at the ready, when out of the woods, going full bent came a beautiful antlered deer - and straight for Chet! The deer passed fifteen feet in front of him, and Chet, with his gun held at his side blasted five shots straight into the air above him. "Did I get him?" he yelled, as he fell off the stump, shaking all over as if in a chill. "Get him?" - he never had his gun at his shoulder and his lead went into the air at a 450 angle. He never did believe it when I described his actions.

Lumberjack meals in those days were good, and most filling - even Dick would have been satisfied. The old camp cook spent many hours baking doughnuts, thick heavy cookies and pies. I recall seeing over twenty pies on the shelf one Sunday before the noon meal. Breakfast was normally at six, dinner (not lunch) at twelve, and supper at six. In the cook camp were long, wooden tables with benches on the four sides, each seating about twenty men. The table cloth was checkered red and white - no napkins - not even paper towels. Plates were tin and knives, forks, and spoons were tin. All along the center of the table were bottles of catsup, vinegar, mustard, pickles, etc., and of course salt and pepper. Breakfast would consist of bacon or ham, potatoes, pancakes, bread, and black Coffee - no eggs - too expensive - oleo - no butter. Always piles of fried cakes and cookies were stacked up in the center of the table as extras. Dinner would be some meat, boiled or fried, (no soup) baked beans, (oh, the catsup that poured over them!) sauerkraut or rutabagas, or both, fried potatoes and usually pie and black coffee. (No ice cream or light desserts.) It seemed to me that everything - almost - was fried. Supper would be baked beans, again, (a woodsman's favorite) plus a pot roast, fried potatoes and usually a root vegetable, plus pie. Those guys could eat pie three times a day. There was little difference between dinner and supper, except that there were no extras such as cookies and fried cakes. Dainty dishes there were none, no salads, no ice cream, no eggs (or rarely) and little but canned fruit. During the meal, there was no talking, it was taboo -- one of the rules of the camp. Not a sound but the din of knives and forks and the noises of gulping and swallowing. The cook and his helper had a lot of work to do, a lot of dishes to wash and he wanted the men to come in, gulp down their food, and get out. This was a Sunday rule too, only on Sundays the fare might include chicken, or a fried steak (everything seemed to be fried), and possibly bananas for dessert. Once in a while -- probably once or twice a month, some fresh fried eggs.

Lost in the Woods - One fall in the early 60's, our hunting party was in full swing and Percy Loud and I were hunting far down the Schneider Road. It was a beautiful day with unusual coloring that fall. As we turned back toward the Tunnel Trail in the twilight, I said: "Perc, I'm going to angle off on this deer runway, you continue up the road and I'll meet you on the Tunnel Trail or at the Lodge." He grunted "OK" and I turned off on the deer runway which wound half a mile thru thick woods, then petered out on the edge of a swamp. Balked, I checked my compass, then turned N.W. and walked to Tunnel Trail and then, as it was getting dark, went on to the Lodge. An hour passed and it got quite dark, everyone was home, cocktails were on the table, dinner was finally announced - and no Perc. Betty got excited, we got nervous, dinner was bolted down, it was dark as pitch outside, and still no Perc.

We all got flashlights and walked down Tunnel Trail, the Wilwin road, the Village road, and far out on the Schneider road, shooting our- guns and yelling our - heads off; I thought you could hear us at Trout Lake - but no Perc. By nine o'clock, Betty could hardly hold back the tears and we were all wondering "What the hell?" I visioned a heart attack. I don't know what the others thought. Perry alerted the Conservation Officer at Trout Lake and he called up the State Police, saying: "Another hunter lost at Wilwin." (We had several lost during our- hunting years, but none overnight before.) Well, the police came, and the conservation officers came, and by eleven, we had six or eight of us combing the woods roads by flashlight, yelling our heads off, and shooting everywhere. It sounded like the Battle of the Marne. Nothing doing - no Perc. We drank coffee, smoked our heads off, roamed the woods, drank more coffee and so on, far into the night. At 1 A.M., the officers left, saying: "If he isn't found by ten tomorrow, we'll alert the army base at Kinross and they'll send out a helicopter to aid the search.

No one slept that night; the women were comforting Betty and the men were over coffied, over smoked, and over tired. About 3 A.M., Betty rushed out of her room, saying she had heard a shot in the woods. No one else had, but we humored her. At daylight, we were up and Rosey and Betty decided to run the car down the Wilwin road as far as M48, blowing the horn all the way in the hope that Perc would hear them and find his way out of the woods. They traveled slowly along about 3-1/2 miles, almost to M-48, when they saw a man walking toward them on the road. It was Perc, tired and much the worse for wear, but smiling and undaunted.

He told them he had suddenly decided to follow me up the deer runway the previous afternoon, so he left the road and hiked in my wake, hoping to overtake me. Like me, he came to the end of the trail in the heavy timber, couldn't raise me by yelling, he thrashed around a bit and decided Wilwin was only a little way off, to the left, thru the timber. (It was over 1� miles off and further to his left.) He had no compass and wasn't quite sure where he was, but he struck out boldly thru the woods and right down into the swamp on the other side. By this time, the sun had gone down and he couldn't tell east from west; he wandered around, trying to get to high ground, until dark. Then he sat down next to a tree to "think his way out." He couldn't. He fired his gun off until he had only two shells left and he yelled his head off, but no use; he was stuck for the night with no compass, no matches, no coat, no nothing.

All during the night, he kept jogging around the tree and doing setting-up exercises to keep warm. He heard more animals and more bird noises and cries than he had ever heard in daytime and sensed some animal close to him - probably a deer. He fired one more shot "when it got still toward morning" and that is the one Betty must have heard.

When dawn came, he picked out East, stumbled out of the swamp and staggered

his way to M48 about four miles from Wilwin. Had he known the country better

and gone West, he would have hit the Schneider road within half a mile and then

Wilwin was only 1� miles away, cutting off two miles on the return trip.